Hamlet

Crafting Madness

Shakespeare Miami, Pinecrest Gardens, Pinecrest, Florida

Saturday, January 13, 2018, J–2&4 (middle of amphitheater), A–17&19 (front left)

Directed by Colleen Stovall

The Shakespeareances.com Canon Project: 38 Plays, 38 Theaters, 1 Year

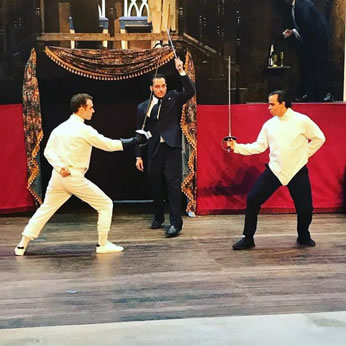

Hamlet (Seth Trucks, left) faces off with Laertes (Lito Becerra) as Horatio (Daniel Rodriguez) referees at the climax of Shakespeare Miami's production of William Shakespeare's Hamlet. Below, Shalia Sakona as Ophelia sews in her chamber. Photos by Colleen Stoval, Shakespeare Miami.

The Ghost leaves. Hamlet follows. Horatio and Marcellus run after, but Marcellus pauses, turns to the audience, and says, "Something is rotten in the state of Denmark." The audience laughs. Miguel Garcia gives a perfectly suitable reading of the line, mingling fear and foreboding, but the audience is hearing a timeworn cliché; to them it's a joke that the playwright plopped into the script at this moment.

That playwright, William Shakespeare, plopped a lot of clichés into his play, Hamlet, albeit they didn't become clichés until the play made them so by attaining a status as one of the greatest literary achievements of the Western World. Theaters taking on Hamlet have to grapple with presenting a play everybody knows so well without it coming off as a string of aural and visual clichés. Shakespeare Miami's 1920's Denmark-set production, helmed by Colleen Stovall, the company's founder and producing artistic director, embraces some of these moments and brushes aside one of the play's most famous sequences. At other points, however, Seth Trucks as Hamlet burrows deep into the essence of the moment, surfacing the truths from which some of theater's most iconic passages and visual images evolved.

Back to my comment about a play "everybody knows so well." Not this audience. Laughing at Marcellus's line is one thing, but the audible shock murmuring through the audience when Polonius (Doug Wetzel) falls dead after Hamlet has stabbed him through the curtain indicates a patronage unfamiliar with the play, though Stovall's textual tweak heightens the scene's impact: Polonius's "O, I am slain!" is delayed two lines, coming after Hamlet wonders if he has stabbed the king and pulls the curtain to reveal Polonius as he falls. Nevertheless, Shakespeare Miami's existence and modus operandi is predicated on a community that doesn't get enough Shakespeare. The company tours its productions to four public parks in South Florida for free showings over four successive winter weekends, supplemented by school matinees and workshops. The company's mission is to make Shakespeare accessible to anyone, no matter their income, education level, or where they live. "That's why we take our shows to the different communities," Stovall says, those communities being Boca Raton, Pinecrest, Coconut Grove, and Hollywood.

The weekend we caught the production it had set up its temporary residency in the amphitheater of Pinecrest Gardens, the former site of the theme park Parrot Jungle. Where once raptors flew inches over my head from the rafters to the stage, Hamlet sets the mousetrap for his uncle and king, Claudius (Adolfo Herrera). The gardens now serve as the Village of Pinecrest's community center, and audiences wander in and out of the matinee performance (as do a flock of peacocks on a roof next to the stage, though a couple of peahens pause in their pecking to settle in at the roof's edge and watch the play for several minutes). For the evening show, the 550-seat amphitheater is nearly full and the audience fully engaged: Trucks gets exit applause after Hamlet's soliloquies "O, that this too too solid flesh would melt" and "O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I," the murmur after Polonius's death is particularly loud, and intended jokes get intended laughs (but Ophelia's death gets an unintended laugh—more on that later).

Stovall strives to stage engagingly entertaining productions. She entered local lore several years ago when she incorporated a rock band of high schoolers into The Taming of the Shrew. She set her Much Ado About Nothing in post–Civil War Michigan (her home state). "I like post-war periods," she tells me. Such is the setting of this Hamlet in a Denmark still recovering from the destruction it suffered during World War I while heading toward capitulation with Nazi Germany during World War II. Stovall's designs (set and costumes, the latter featuring black tuxes and capes, three-piece suits, and jewel-lined gowns and flapper dresses) evoke a Great Gatsby look. Though this sometimes runs contrary to the text—Hamlet's "inky cloak" is the standard fashion in the room—it adds dimensions of subtext to some scenes, especially when Claudius tries to pray. Though he is your typical murdering villain, when he appears and acts as an übercapitalist his lines carry more resonance as, "My stronger guilt defeats my strong intent [to pray], and like a man to double business bound, I stand in pause where I shall first begin." Claudius has violated just about every one of the Ten Commandments—including, in Herrera's portrayal, coveting his neighbor's wife, or at least his neighbor's daughter—on his way to political and economic power, yet he still thinks he might get into heaven if he only prays. "May one be pardoned and retain th'offence?" he wonders; but he finds that he can't even pray.

Much of Stovall's textual changes are subtle, and most of them are intended to get Shakespeare's longest play with three different versions (First Quarto, Second Quarto, and First Folio) down to 2:40 plus intermission. "My job is to cut out approximately 50 percent of the play's 4.5 hour running time while keeping in all of the famous and beloved lines, bits, and, of course, characters," she writes in her director's notes. The most obvious excision is all things having to do with Norway and Fortinbras, whose play-ending lines are spoken by Horatio (Daniel Rodriguez). Osric is gone, too, his message about the proposed fencing duel relegated to a read letter.

Stovall's approach to Ophelia, however, has little to do with length and duration. In addition to her dysfunctional family and her boyfriend's dysfunctional behavior, Shalia Sakona's Ophelia has to put up with Claudius groping her. He proves to be what Hamlet calls him, a satyr: at every encounter Claudius grabs at Ophelia like an octopus with hyperactive tentacles even as she resists his advances and storms out of the court in disgust. Hamlet witnesses many of these episodes, but he ends up becoming a perpetrator himself. She welcomes his romantic advances, even encouraging him to follow her into her chamber during the closet scene (staged without dialogue in this production). Hamlet turns down the invitation and mopes out, whereupon Polonius arrives and Sakona speaks Ophelia's report about her encounter with the prince, which doesn't really match what we've just seen. However, after Ophelia breaks up with Hamlet and he gets abusive with her during his nunnery speech, his antic act before the players perform The Murder of Gonzago includes out-and-out sexual harassment of Ophelia, who is unable to escape or be rescued, though the room is full of lords and ladies.

While Ophelia is a #MeToo heroine, Gertrude (Constance Moreau) is a stereotype airhead. As the players portray Gonzago's murder and the murderer seducing the widow queen, Claudius catches on to the trap Hamlet has set for him; Moreau's Gertrude, however, is thoroughly enjoying the play, and even lets out a squeal of delight when the murderer lands the queen.

In this production, Ophelia doesn't go mad in the mental illness sense. Rather, her madness is one of fury. Stovall contends that Shakespeare's portrayal of Ophelia is unrealistic, saying she's never seen the mad scenes work in any production. To achieve this alternative definition of madness, Ophelia speaks Laertes's lines referring to the nature of their father's burial and Sakona gives a cynicism-dripping reading of Ophelia's songs. Of course, the play's plot wouldn't allow Laertes to see his sister as merely angry rather than driven to insanity, nor does a temper tantrum fit the report of Ophelia's drowning. Stovall works around this obstacle by significantly altering "mad" Ophelia's second appearance and the means of her death. In the first of the two "mad" scenes, Ophelia rails at Gertrude and Claudius with Horatio in attendance, directing her "I thank you for your good counsel" to Horatio, a loaded comment considering the context, though Horatio responds with a blank stare. When Ophelia returns to the stage, Claudius is alone. As Ophelia rages, yanking flowers off of Gertrude's discarded hat and throwing them at Claudius, he tries to kiss her. She violently resists, and he snaps her neck—witnessed by a shocked Gertrude, who has entered on the set's upper level as this scene unfolds. Given her behavior while watching The Murder of Gonzago, this Gertrude has hitherto been clueless of Claudius's criminal ways.

She still delivers the famous description of Ophelia's death, but it's become an enforced alibi. Gertrude enters to Laertes with the start of her line, "One woe follows on another—" but stops when she sees the King standing there (he and Laertes have been plotting the murder of Hamlet). Gertrude continues her description of Ophelia drowning as Claudius walks over to her, puts one arm around her shoulder and the other as if comforting her heart but actually poised near her throat. She's seen what he can do with that hand, and she carefully tells Laertes of his sister's death. "Alas, then, she is drown'd?" he says quietly. "Dead," Gertrude replies. "Drown'd," Claudius says with intense affirmation, as much for his wife's sake as for Laertes. "Drown'd," Gertrude repeats.

Laertes (Lito Becerra) receives much more respect in this staging than I'm accustomed to seeing, and I appreciate that. Becerra brings a casually friendly attitude to Laertes, one who can barely tolerate his father's precepts. From his and Ophelia's behavior while Polonius is delivering his famous speech, they've heard it all before—except the last bit about "to thine own self be true," which strikes Laertes as particularly profound coming from his father. During the banquet in Scene Two when Claudius announces that Hamlet is his heir, Laertes reaches around behind Ophelia, sitting between them, to clap Hamlet on the shoulder. For his leave-taking scene, Laertes walks on stage as Hamlet is giving Ophelia a love letter, coughs to announce his presence, and then directs the "farewell" of his opening line to Hamlet, who nods in return, before addressing his sister.

Rodriguez's Horatio is every bit Hamlet's good buddy, a wingman not only to his plot to entrap the king but appreciating the prince's treatment of Rosencrantz (Jeremy Wershoven) and Guildenstern (Schafer Ross). As Hamlet reports after he sends them to their deaths, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern do make love to their employment in this production. Upon their arrival at the court, Claudius bestows medals on them in a formal ceremony, and it's in spying these medals (which they try to cover up with their cloaks) that inspires Hamlet to inquire into their presence in Elsinore. There's nothing comic about their portrayals; the two sycophants take on a peremptory tone with Hamlet, and the comedy comes in how the prince reminds them of his royal status. Wershoven and Ross double as the gravediggers (well, Wershoven does; the other gravedigger is here a buttoned-up sexton), and Wershoven shows his comic potential in his delightful turn singing as he tosses bones about and bandying with Hamlet.

The part largely unchanged is that of the title character, and yet Trucks gives one of the most cliché-free performances of Hamlet I've seen, especially in his soliloquies. In the first of his famous speeches, Hamlet moves to the side of the stage as the royal banquet concludes and the women presumably retire to the parlor while the men stay behind with their cigars and brandy. Trucks then moves up to a low wall fronting the stage to speak directly to the audience. He follows the first line of his soliloquy, "O, that this too too solid flesh would melt, thaw, and resolve itself into a dew!" with a more poignantly read second line: "Or that the Everlasting had not fixed his canon 'gainst self-slaughter." Suicide is never far from this Hamlet's thoughts, so much has the life he's known gone awry. This soliloquy serves as a backstory to Hamlet's emotional state, detailing his father's death and his mother's hasty marriage to her brother-in-law and what a disgusting man Hamlet considers Claudius (Hamlet doesn't yet know his father was murdered). As Trucks delivers this speech he glances back at Claudius carousing with the other men on the stage. Turning this opening soliloquy into a visual narration is an effective device.

The part largely unchanged is that of the title character, and yet Trucks gives one of the most cliché-free performances of Hamlet I've seen, especially in his soliloquies. In the first of his famous speeches, Hamlet moves to the side of the stage as the royal banquet concludes and the women presumably retire to the parlor while the men stay behind with their cigars and brandy. Trucks then moves up to a low wall fronting the stage to speak directly to the audience. He follows the first line of his soliloquy, "O, that this too too solid flesh would melt, thaw, and resolve itself into a dew!" with a more poignantly read second line: "Or that the Everlasting had not fixed his canon 'gainst self-slaughter." Suicide is never far from this Hamlet's thoughts, so much has the life he's known gone awry. This soliloquy serves as a backstory to Hamlet's emotional state, detailing his father's death and his mother's hasty marriage to her brother-in-law and what a disgusting man Hamlet considers Claudius (Hamlet doesn't yet know his father was murdered). As Trucks delivers this speech he glances back at Claudius carousing with the other men on the stage. Turning this opening soliloquy into a visual narration is an effective device.

Trucks approaches "To be or not to be" in a rush, the actor giving the lines an almost obligatory brush, shrugging to the audience as if to say, "OK, if I have to I'll speak the speech, but let's do it fast." He pauses, however, when he hits "To sleep—perchance to dream." He's a man suffering depression to a degree that to "end the heartache and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to" is "devoutly to be wished"; he already dreams. Bad dreams. I write from my own experience here, and pondering an eternity of such dreams is enough to waylay anybody from ending a calamity of so long a life.

With Hamlet's final soliloquy, the thematic and emotional power beneath the Hamlet-and-the-skull cliché emerges in Trucks' rendering of Hamlet recalling his fond childhood memories that he sees in, literally, the face of death. What is life but a slow, troublesome trek to such an ending? Though Hamlet has seen and talked to his father's ghost, he here questions the existence of an afterlife. He begins the scene ridiculing the skulls that the gravedigger tosses onto the ground, justified ends of what Hamlet imagines could have been politicians and lawyers. When he learns that one of those skulls is actually that of his beloved Yorick, he perceives that even the greatest and worthiest of people—Alexander and Caesar, for example—end their existence in such a state.

Miami Shakespeare's Hamlet, though, ends in a state of theatrical scintillation with the climactic fencing duel between Hamlet and Laertes. Simply put, this is one of the best stage combat sequences I've ever seen. The fencing itself is exquisite, the whole battle is imbued with the personalities of Trucks' feigning-mad Hamlet and Becerra's feigning-courteous Laertes. When the fight gets intense the increasingly desperate swordplay up and down and across the set is supplemented by effective punches. It lasts at least five minutes, and even that is too short.

Eric Minton

January 18, 2018

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances