Really, He's a Guy You Might Like

The Friendly Shakespeare:

The Friendly Shakespeare:

A Thoroughly Painless Guide to the Best of the Bard

Norrie Epstein (Viking, 1993)

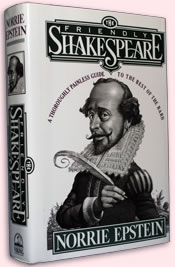

Shakespeare has a prankish look in Mark Summers' illustration gracing the hardback cover of Norrie Epstein's book The Friendly Shakespeare. The playwright's right hand holds a quill in a way that indicates he had just written something silly or cynical, or maybe it's a sly riposte he's awfully proud of. The slight grin forming underneath his handlebar mustache and the gleam in his eyes tell you he can't wait for you to read it. Summers' drawing offers no hint of deity or historical perspective in his Shakespeare, and as such it is the ideal jacket cover for Epstein's lighthearted yet respectful summary of all things Shakespeare.

Epstein's book is not a biography. It is not a collection of critical essays. It is not a study guide for students, nor is it “a coffee table book extolling the beauties of the Bard with glossy pictures of Anne Hathaway's cottage” (her words). Epstein's aim is to introduce readers to “the Shakespearean spirit in all its forms, from the commercialism of Stratford to the lyricism of Romeo and Juliet.” This Thoroughly Painless Guide to the Best of the Bard is more of an omnibus of Shakespeare culture: the culture he lived and wrote in, the culture of his plays, the generations of cultures in which his plays have been embraced, and, in turn, the culture his genius created.

“Shakespearean spirit” is the key phrase here. Epstein sees a man who revealed a keen sense of humor in all his plays. She therefore takes him to be a playwright who didn't take himself too seriously, who probably would smirk incredulously at the scholarship his writing has generated and the industry that has grown up around his works, let alone his birthplace (in that cover illustration, he is kind of smirking). Shakespeare's own seeming attitude inspires her to write with a breezy humor while eschewing any academic approaches to her subject. “For the most part I avoid plot summaries, because they are boring to read and tedious to write,” she admits in her introduction. “(And besides, plot summaries are rarely helpful in understanding Shakespeare's genius, since for the most part he didn't invent his own plots.)” Right there, you get Epstein's irreverent attitude even as she makes an insightful observation.

Although the book is now almost 20 years old and I hadn't cracked it open in many years, The Friendly Shakespeare is in some ways a prototype to Shakespeareances.com. Heck, I even have a caricature of Shakespeare on my “cover,” too. That's why I not only recommend it for any Shakespeare library, I think it should be the third purchase, after a collected works and a viable biography. Epstein's book is a perfect gift for someone who loathes Shakespeare—because she introduces Shakespeare and his plays in the context of how and why they became so popular while poking fun at the Bardolotry that inspires so much Shakespeare hatred. Those who love Shakespeare will appreciate Epstein's appreciation of his genius while at the same time learning from and laughing at her insights into his works or his works' legacies.

She opens the book with discussions on Shakespeare's ongoing popularity and unpopularity. The chapter “Why Is Shakespeare So Popular?” is all of two pages and is followed by another two-page chapter titled “Why Is Shakespeare Boring?” She tackles, briefly (everything is brief in this book), the issue of properly teaching Shakespeare in the schools. In this respect, the book shows its age because new teaching methods are sparking fervent interest in Shakespeare among teens across the country. Still, she makes an evergreen observation that one of the chief culprits to anti-Shakespeareanism is the inclusion of Julius Caesar in high school curricula, “one of the most austere and static of all Shakespeare's plays [which] probably has the distinction of turning away more students from Shakespeare than any other play.” Originally, the play was coupled with Latin lessons, she writes, but while Latin gradually disappeared from America's high schools, et tu Caesar hung around. Why? “It's short, and it has no sex,” writes Epstein.

Epstein whips through Shakespeare's biography and his non-biography (i.e., the authorship question), liberally flavoring the book with quotes and sidebars,. She groups the plays into their genres but doesn't dwell on every play. Only The Tempest gets much attention in the section on the tragicomic romances (vice Pericles, The Winter's Tale and Cymbeline), while, interestingly, Troilus and Cressida makes up the lion's share of the section on the Problem Plays. Read Epstein's take on this Trojan War tale and its locker room humor and you might find yourself embracing it as the finest example of Shakespeare's timeless genius.

This doesn't mean she gives hoity-toity slights to The Bard's most enduringly popular plays. Twelfth Night gets seven pages in The Friendly Shakespeare (relatively speaking, that's encyclopedic in comparison to other entries), broken up into sections on characters, setting, and Shakespeare's use of time. The chapter on Twelfth Night is followed, logically, by a chapter on “Comedy in Drag,” which then leads (not so logically) to a chapter on “Anachronisms” in Shakespeare's plays, and then (resuming some sense of logic) a chapter on “Playing Havoc with the Bard” (on the ideology of altering the settings for Shakespeare's plays), which naturally leads into a chapter on “Updating Shakespeare.” Epstein devotes a Tolstoyian 36 pages to Hamlet, but much of that covers such associated topics as Hamletology, how to play Hamlet (with quotes from and about famous Hamlets), parodies and adaptations of Hamlet, and Hamlet controversies such as “Is Hamlet Insane?” and “Is Hamlet Fat?”

Epstein caps off her 550-page tome with “The Spin-Offs,” looking Shakespeare movies, music, television, and merchandise, the “Shakespeare Industry,” and “Great Moments in Bardolatry” (did you know there was a book called Shakespeare's Knowledge of Chest Diseases?). If it sounds like something of a jumble, that's not unintentional. “Don't feel compelled to read this book from cover to cover,” Epstein writes in her introduction: “it's meant to be dipped into and browsed through at your leisure, because Shakespeare should never be a duty.”

As a lecturer of literature at the University of California and other colleges, Epstein has encountered plenty of people who loathe Shakespeare. Though she has myriad reasons to admire his works, rather than try to explain “what makes a [Shakespearean] line or a speech so wonderful,” she concludes that “Shakespeare is good because he is true.” She has realized, over the years, that Shakespeare constantly seems to be in her conscious, commenting on many of her day-to-day experiences, ideas, and memories. “We can still put Shakespeare's words in our mouths,” Epstein writes, “and be true to our own experience.”

If the book has an overriding fault, it's merely the fact that it's almost 20 years old. It's not that the cultural references are dated, but that two decades' worth of movies, spin-offs, bardolatry, and havoc-playing have passed on which I would love to have Epstein comment. I grant that those who prefer their Shakespeare confined to the altars of academia will consider her tone too whimsical and her scholarship too light. That's OK, because those people are not her audience; the rest of us are, both those who enjoy hanging out with Shakespeare in the theater and the pub afterward, and those who are afraid to meet him.

Eric Minton

May 20, 2012

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances